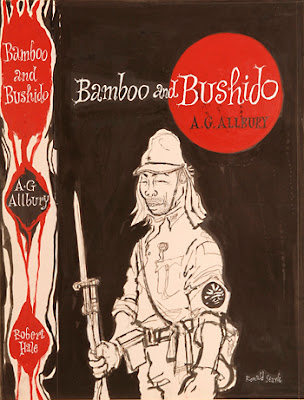

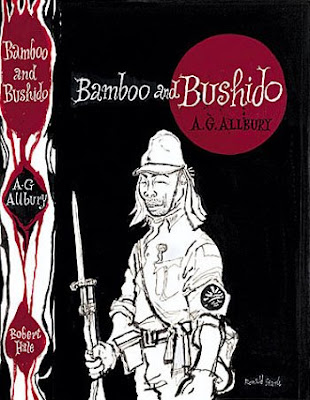

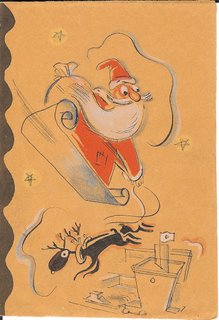

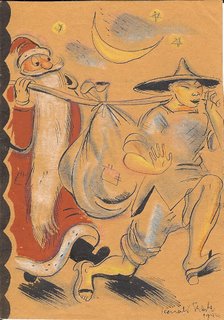

PEN INK, WATERCOLOUR AND BODYCOLOUR

15 X 11 3/4 INCHES

ILLUSTRATED: A G ALLBURY, BAMBOO AND BUSHIDO, LONDON: ROBERT HALE, 1955, DUSTJ

The 'Lofty Cannon Collection', State Library Victoria.

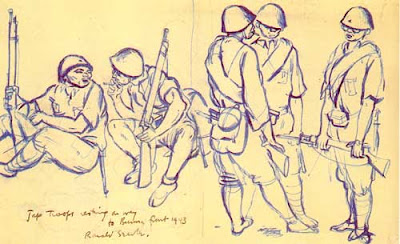

This collection comprises a book of sketches by English artist Ronald Searle and letters between Searle and fellow soldier Henry 'Lofty' Cannon.

The sketches were produced while Searle and Cannon were prisoners of war on the Thai-Burma railway and at Changi prison camp during World War II (1943-46). They depict scenes of camp life, showing the hardship of life as a POW and highlighting Lofty Cannon’s medical service to fellow POWs.

Searle kept his sketches safe by hiding them under the mattresses of prisoners suffering from cholera. He took the surviving drawings home with him after he was liberated in 1945. They were published in The Naked Island (1951), written by fellow POW Russell Braddon.

The sketches within the State Library’s collection were given with great gratitude by Ronald Searle to Lofty Cannon. This can be seen in Searle's comment to Lofty in a letter from 30 August 1946: 'I know, as you do, that you helped to save my life and made my existence under that net almost bearable. Believe me, Lofty, I’ve praised the stars that brought you to that ward many times.'

'I am just learning about Ronald Searle, as I have just recently learnt of his connection to my late grandfather Lofty Cannon - the subject of some of his illustrations. Although I do not have the information at hand right now, I recall reading that Searle drew with his non-preferred hand when he was a POW when he was very ill (drifting in and out of a coma) because his left hand (preferred hand) was covered in ulcers. I don't know if this helps to explain why perhaps you think the Japanese POW drawings are of a different standard to his previous work....? Perhaps you knew that already?'

Anon. http://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2006/11/ronald-searle.html

Ronald Searle was born in Cambridge, England, in 1920. In 1939, he joined the army as an architectural draftsman. At the fall of Singapore he became, with so many other British and Australian troops, a prisoner of war in Changi and on the Thai Burma railway. During this time Ronald Searle never stopped drawing. After the war, Ronald Searle became one of the foremost illustrators in England and Europe, and in the United States he was the first non-American cartoonist to receive the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben Award. He is more popularly known as the creator of the St Trinians and Nigel Molesworth (with Geoffrey Willans) cartoons. Australian Henry Judge (Lofty) Cannon became a friend of Ronald Searle when he was a medical orderly with the 2/9th Field Ambulance and fellow prisoner of war.

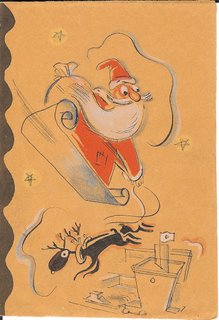

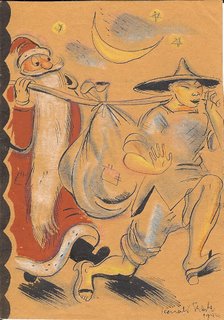

Scans of these Christmas cards were sent to me by David McCarthy who had inherited them. They have been verified by the Imperial War Museum as genuine Searles.

To The Kwai - And Back; war Drawings 1939-1945, by Ronald Searle, Souvenir Press, April 2006, 192 pages, ISBN 0285637452, £25.

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Ronald Searle, the creator of the girls of St Trinians and one of the ablest and most famous British cartoonists, was a prisoner of war of the Japanese from February 1942 to August 1945. With determination and courage he managed to keep a record in drawings of his years of suffering as a prisoner in Singapore and on the Burma-Siam Railway. He describes the sketches in this book as "the graffiti of a condemned man, intending to leave a rough witness of his passing through, but who found himself - to his surprise and delight - among the reprieved." These drawings selected from the originals which he succeeded in bringing home are now part of the collection of the Imperial War Museum in London. They are harrowing and moving.Ronald Searle's narrative is spare and restrained. The story begins with his joining the army as a volunteer in April 1939 as he realised that war with Nazi Germany was inevitable. He was a sapper in the engineers and remained a private soldier to the end. His unit was sent to Singapore where he arrived on 13 January 1942. They were untrained and unequipped for jungle warfare. His unit was ordered forward to destroy everything in front of the advancing Japanese forces. It was, he said, "a scorched arse policy" and the Japanese "moved forward to chop into small pieces all the wounded that had to be left behind." Singapore which had suffered from "years of inept, incoherent and chaotic political and military mismanagement" by the British lay at their mercy but the Japanese forces showed no mercy. "It is estimated that 20,000 Chinese alone were shot or beheaded during the first few days after capitulation." Searle drew two gruesome sketches of severed heads on poles and on shelves. (See drawings on pages 66 and 67).

The first few months in prison camp were bad. They were made to wear armbands with an inscription in Japanese which Searle was told meant "One who has been captured in battle and is to be beheaded or castrated at the will of the Emperor." Food was increasingly scarce (at best 400 calories a day). Flies swarmed and disease was rife. They were forced to sign an undertaking not to try to escape. The Japanese General in command of the camps had no intention of abiding by the Geneva Conventions. Some prisoners were sent to Japan. Searle was one of a batch of 3,270 selected to work on the Burma-Siam railway. "Skinny, undernourished, suffering from a variety of tropical skin diseases and deficiency sores" they were destined to march 160 kilometres into the jungle, to chop a railway through granite mountains and some of the most dense vegetation in the world…Two-thirds of our group died before the end of the year." The guards "clubbed those who began to fall behind the rest of our ragged column." "The forced marches continued through the nights and memories of them have become a compression of smells and feelings; plodding along a glutinous track thick with pitfalls, faces and bodies swollen and stinging from insect bites and cuts from overhanging branches that whipped back at us." If at roll call the total was short "it meant a thrashing for someone with the ubiquitous bamboo stick - and being beaten with bamboo is like being beaten with an iron bar." Their "working methods were barely out of the stone age " and their conditions were made worse by the flies, the mosquitoes, the lice and the bedbugs and the very inadequate rations. "Some of our overseers had an extremely primitive sense of humour. During the noon break on the cuttings, they would frequently relieve their boredom by calling us into line before we had barely gobbled down our rice, to watch the torture of one of us picked at random. The unlucky one might be made to hold a heavy rock above his head in the full sun, with a sharpened bamboo stick propped against his back. If he wavered, which he inevitably did, the bamboo spear pierced his skin" (see drawing on page 114).

"In a tent which housed the dying and where the sketches on these pages were made, I think I reached rock bottom. Between bouts of fever I came round one morning to find that the men each side of me were dead, and as I tried to prop myself up to get away from them, I saw that there was a snake coiled under the bundle on which I had been resting my head."Eventually he was returned to Singapore to the horrifically overcrowded Changi jail to work on levelling the ground for a military base or to work in the docks. He managed to escape the attentions of Kempeitai who had their own prison in Outram Road, but he was always afraid that his sketches would be found. Fortunately for him the Japanese were very frightened of cholera and cholera sufferers helped to hide his drawings.Some among the Japanese guards did show a little kindness. One named Ikeda spotting Searle sketching showed him photographs of his family and asked for a sketch of himself to send to his mother, There was also a Captain Takahashi, who summoned Searle and three other sappers to work at his house, drew a mother and child in Searle's sketchbook and confessed that he too was an artist who had been studying in Paris when he "was called home to this - ah - to serve…" He then gave Searle a handful of coloured pencils and wax crayons. Searle would like to have made contact with him but had no success.On 15 August 1945 the Japanese authorities "announced that although Nippon had agreed to unconditional surrender, Field Marshal Count Terauchi, Commander-in-Chief of the Southern Army, did not associate himself with it and intended to fight on. What we did not know then was that a plan existed at Count Terauchi's Saigon headquarters to execute all prisoners in case of invasion." British Forces were indeed massing for an attack on Malaya, the so-called operation "zipper." Fortunately for all of us sense prevailed, but it was not until 28 September 1945 that Ronald Searle finally boarded a ship for home.There can be no doubting Searle's story. His drawings are a vivid testimony of the truth and of the suffering of so many. I wish that Japanese historical revisionists and Japanese nationalists would read this book. They might then begin to understand why we object to Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi and Foreign Minister Taro Aso paying their respects at the Yasukuni shrine where the Yushukan museum glorifies war and the Japanese military. They should be remembering all those who died and suffered during the war including the civilian dead in Singapore and, of course, in Japan itself.

To The Kwai - And Back; war Drawings 1939-1945, by Ronald Searle, Souvenir Press, April 2006, 192 pages, ISBN 0285637452, £25.

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Ronald Searle, the creator of the girls of St Trinians and one of the ablest and most famous British cartoonists, was a prisoner of war of the Japanese from February 1942 to August 1945. With determination and courage he managed to keep a record in drawings of his years of suffering as a prisoner in Singapore and on the Burma-Siam Railway. He describes the sketches in this book as "the graffiti of a condemned man, intending to leave a rough witness of his passing through, but who found himself - to his surprise and delight - among the reprieved." These drawings selected from the originals which he succeeded in bringing home are now part of the collection of the Imperial War Museum in London. They are harrowing and moving.Ronald Searle's narrative is spare and restrained. The story begins with his joining the army as a volunteer in April 1939 as he realised that war with Nazi Germany was inevitable. He was a sapper in the engineers and remained a private soldier to the end. His unit was sent to Singapore where he arrived on 13 January 1942. They were untrained and unequipped for jungle warfare. His unit was ordered forward to destroy everything in front of the advancing Japanese forces. It was, he said, "a scorched arse policy" and the Japanese "moved forward to chop into small pieces all the wounded that had to be left behind." Singapore which had suffered from "years of inept, incoherent and chaotic political and military mismanagement" by the British lay at their mercy but the Japanese forces showed no mercy. "It is estimated that 20,000 Chinese alone were shot or beheaded during the first few days after capitulation." Searle drew two gruesome sketches of severed heads on poles and on shelves. (See drawings on pages 66 and 67).

The first few months in prison camp were bad. They were made to wear armbands with an inscription in Japanese which Searle was told meant "One who has been captured in battle and is to be beheaded or castrated at the will of the Emperor." Food was increasingly scarce (at best 400 calories a day). Flies swarmed and disease was rife. They were forced to sign an undertaking not to try to escape. The Japanese General in command of the camps had no intention of abiding by the Geneva Conventions. Some prisoners were sent to Japan. Searle was one of a batch of 3,270 selected to work on the Burma-Siam railway. "Skinny, undernourished, suffering from a variety of tropical skin diseases and deficiency sores" they were destined to march 160 kilometres into the jungle, to chop a railway through granite mountains and some of the most dense vegetation in the world…Two-thirds of our group died before the end of the year." The guards "clubbed those who began to fall behind the rest of our ragged column." "The forced marches continued through the nights and memories of them have become a compression of smells and feelings; plodding along a glutinous track thick with pitfalls, faces and bodies swollen and stinging from insect bites and cuts from overhanging branches that whipped back at us." If at roll call the total was short "it meant a thrashing for someone with the ubiquitous bamboo stick - and being beaten with bamboo is like being beaten with an iron bar." Their "working methods were barely out of the stone age " and their conditions were made worse by the flies, the mosquitoes, the lice and the bedbugs and the very inadequate rations. "Some of our overseers had an extremely primitive sense of humour. During the noon break on the cuttings, they would frequently relieve their boredom by calling us into line before we had barely gobbled down our rice, to watch the torture of one of us picked at random. The unlucky one might be made to hold a heavy rock above his head in the full sun, with a sharpened bamboo stick propped against his back. If he wavered, which he inevitably did, the bamboo spear pierced his skin" (see drawing on page 114).

"In a tent which housed the dying and where the sketches on these pages were made, I think I reached rock bottom. Between bouts of fever I came round one morning to find that the men each side of me were dead, and as I tried to prop myself up to get away from them, I saw that there was a snake coiled under the bundle on which I had been resting my head."Eventually he was returned to Singapore to the horrifically overcrowded Changi jail to work on levelling the ground for a military base or to work in the docks. He managed to escape the attentions of Kempeitai who had their own prison in Outram Road, but he was always afraid that his sketches would be found. Fortunately for him the Japanese were very frightened of cholera and cholera sufferers helped to hide his drawings.Some among the Japanese guards did show a little kindness. One named Ikeda spotting Searle sketching showed him photographs of his family and asked for a sketch of himself to send to his mother, There was also a Captain Takahashi, who summoned Searle and three other sappers to work at his house, drew a mother and child in Searle's sketchbook and confessed that he too was an artist who had been studying in Paris when he "was called home to this - ah - to serve…" He then gave Searle a handful of coloured pencils and wax crayons. Searle would like to have made contact with him but had no success.On 15 August 1945 the Japanese authorities "announced that although Nippon had agreed to unconditional surrender, Field Marshal Count Terauchi, Commander-in-Chief of the Southern Army, did not associate himself with it and intended to fight on. What we did not know then was that a plan existed at Count Terauchi's Saigon headquarters to execute all prisoners in case of invasion." British Forces were indeed massing for an attack on Malaya, the so-called operation "zipper." Fortunately for all of us sense prevailed, but it was not until 28 September 1945 that Ronald Searle finally boarded a ship for home.There can be no doubting Searle's story. His drawings are a vivid testimony of the truth and of the suffering of so many. I wish that Japanese historical revisionists and Japanese nationalists would read this book. They might then begin to understand why we object to Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi and Foreign Minister Taro Aso paying their respects at the Yasukuni shrine where the Yushukan museum glorifies war and the Japanese military. They should be remembering all those who died and suffered during the war including the civilian dead in Singapore and, of course, in Japan itself.

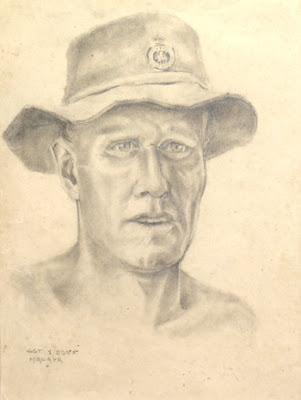

Portrait of Ossie

SIGNED WITH INITIALS, INSCRIBED 'SGT1/SSVF MALAYA' AND DATED 'JAN '44'

PENCIL 6 X 4 1/2 INCHES (Drawing NOT by Searle)

Prisoners hauling logs to gaol, Changi prison © Ronald Searle 1944, by permission of the artist and The Sayle Literary Agency.

'I have just come back from MW’s room, he has invited three artist lads up with some sketches, one of these was S, who draws for Lilliput and Men Only. He gets £7 per drawing, - rapid pen and ink stuff- and other work too. He has done lots and lots of rough sketches in camp and he’s now working on some murals at the cinema here. We have agreed to start an Artists’ Circle in my Chinese Temple on Sundays starting next Sunday at 10.30 and he is bringing a good Java model. There will be about six of us. I am very bucked about it.'

From the diaries of Thomas George Cotterell