(Brian Sibley found this in Private Eye)

Getting The Joke: Ronald Searle

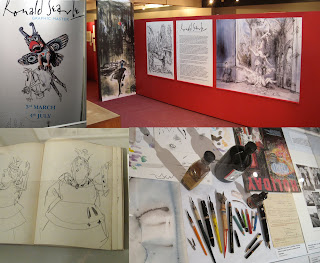

Cartoonists from Gerald Scarfe to Steve Bell genuflect to the work of Ronald Searle. His illustrations have appeared in publications around the world, from Life to Le Monde. Yet in his native country, apart from by his fellow artists, he remains curiously undervalued. To mark his 90th birthday, a new exhibition (Ronald Searle: Graphic Master) at the Cartoon Museum sets the record straight.

Jack Watkins profiles ‘our greatest living cartoonist’.

In Russell Davies’s biography of Ronald Searle, he makes some barbed references to British journalists who seem to think that his subject’s work begins and ends with the St Trinian’s drawings and the film credits he drew for the cinema. The frustration is understandable. However, it’s unlikely that Davies will read this feature, and Searle himself now lives in Provence, so, with one last nervous scan of the horizon just to make sure, I think it’s safe to write that, for the great unwashed among us, it is through the TV re-runs of these films – and the equally delightful Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, and Monte Carlo or Bust – that Searle is chiefly familiar.The fact is that the great man has resided in France for nearly fifty years, and while he is still highly regarded here by the artistic community – and received official recognition in the shape of a CBE in 2004 – his profile in Britain remains low, and the wider artistic merit of his work has, until now, been somewhat overlooked.

Searle turns 90 this month and his prolific career, which has already lasted some 75 years, is ongoing. Anita O’Brien, the curator of the Cartoon Museum’s retrospective exhibition, recently visited him in Provence, and saw in his meticulously organised studio a reflection of his approach to his work. His appetite for life, his remarkable curiosity, and the intelligence and wit that informs his drawings are all seemingly undimmed.

It’s not enough, of course, to say that all great artists have an immediately recognisable stamp; even mediocrity can wear a badge of identity. But a Searle picture is certainly unmistakeable. The human figures are bird-like – stork legs, beaky noses, and pop-eyes that are often shifty or bewildered – their distortions and wispy lines suiting the mood of feverish anarchy. They are drawings whose skill is perhaps concealed in a feeling of rapidity, an impression that they were quickly set down.

When Searle was eighteen he received a one-year scholarship to the Cambridge School of Art, enabling him to become a full-time art student. He later recalled: “It was drummed into us that we should not move, eat, drink or sleep without a sketchbook in the hand. Consequently the habit of looking and drawing became as natural as breathing.” Perhaps this fast sketching on the move so imprinted itself that it became his signature.

Searle had, in fact, been honing his distinctive style long before that. His background was modest. His father was a porter at Cambridge railway station and his mother took in lodgers to help pay the household bills. Young Ronald had a curious mind, however, devouring books on natural history and archaeology, and haunting the Cambridge museums. Here he encountered caricature art for the first time, in the work of the author and cartoonist Sir Max Beerbohm.

His interest grew in the great cartoonists and satire masters of the past, such as James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank. The Cartoon Museum exhibition includes some examples of their output, as well as Searle’s medals dedicated to the ‘Fathers of Caricature’, designed for the French Mint in the 1970s and 1980s.

Leaving school at fifteen, he took a succession of low paid jobs in order to scrape together money for art classes, succeeded in having a series of weekly cartoons published in the local Cambridge Daily News, and nursed ambitions of a career in Fleet Street. He had an aunt who lived in Bromley, from where he would walk to the then centre of the newspaper industry to try to engender editor interest. “If I took the bus then I couldn’t eat,” he explained. Finally someone listened, and his first illustration in a national newspaper was featured in the Daily Express in 1939.

By now, though, the War had begun and Searle was to enlist with the Royal Engineers. He was stationed in Singapore, but that fell to the Japanese in 1942, and he spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, including time in the brutal Changi Prison and working as enforced labour on the Burma Railway. Among a long list of maladies, Searle suffered beri-beri, malaria, dysentery, boils, ulcers and insect bites – yet, heroically working by fire-light, made drawings of the grim realities of camp life. Some of these fragile ‘secret’ sketches, which he’d concealed from his gaolers by hiding them under the beds of friends dying of cholera, are present in the exhibition. The experience had transformed Searle’s artistic motivations, and suddenly he felt the need to draw “to justify the death of your friends.”

His first collection of St Trinian’s drawings came out in 1948. Enchanting as they and subsequent ones of the delinquent girls are, he also cast his net wider. His caricatures accompanied theatre reviews in Punch, and drawings on current affairs appeared simultaneously in the politically opposed Tribune and the Sunday Express. Searle covered the trial of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann for Life magazine in 1961, around which time he moved to Paris. His watercolours from his travels to places such as Morocco, and his story illustrations for books, show a marvelous sense of detail and atmosphere, and in France – where, up until 2008 he was still drawing a weekly political cartoon for Le Monde – Searle is accorded as a true artist.

It’s a measure of the feeling for him that many illustrators have penned words of appreciation for the 160 page catalogue that accompanies this exhibition. Gerald Scarfe writes of wanting to draw like him. “His pen was always searching, exploring very nook and cranny of his subject. His exciting, electric style fascinated me.” Posy Simmonds argues that he belongs with the masters such as Rowlandson and George Grosz. Perhaps Steve Bell, current upholder of the satirical line in The Guardian, puts it best: “To say he is an artist is no more than the truth, but he is more than that: he is our greatest living cartoonist with a lifelong dedication to his craft… His work is truly international, yet absolutely grounded in the English comic tradition.”

Optima magazine 5th March 2010

Ronald Searle: Graphic Master, Cartoon Museum, London

Scratch, scribble, scrawny, scruffy, scrape, scrawl – Searle's lines often begin with scr-, conveying an abrasive feeling. He is also a comedian, and can fill up a body like a bag of sugar, a helpless sagging blob that swells and slops and spreads. This mixture became his signature mode, the savage and the genial together, and it hasn't failed him in almost seven decades. His retrospective at the Cartoon Museum, "Ronald Searle: Graphic Master", marks his 90th birthday.

His beginnings were first as a juvenile cartoonist, then an art student, then a Japanese POW. He took pen and paper to the verge of death. His image of an emaciated man – Prisoner dying of Cholera, Thailand 1943 – is one of the greatest drawings of the 20th century. And it might have promised a career in serious art. But Searle refused to stick to "seriousness". His most famous works of the 1950s are his illustrations of St Trinian's and St Custard's, where pain is sublimated into a schoolchild's wicked naughtiness. How could the same hand do both?

Another artist might have decided limitation was compulsory; Searle pursued ever more, and ever more confident, variety. The range is amazing: invention, observation, lightness, darkness. Look at the grim and sober reportage of Eichmann's trial in Jerusalem, early 1960s. And then, pretty well simultaneously, there's a Punch cover; a picture of beautifully, innocently absurd birds, with stick-on fluff-ball popping eyes, and a man with a "lobster-claw" head, a long pointed nose one pincer, a long pointed chin the other.

People sometimes ask: can he or she draw? The implication is that there's a single secret. But Searle's performance shows how multiple the matter is. There are so many different ways of being accurate – and then, even more strangely, these different registers can interbreed. The Cartoon Museum is a small space. Its highlights are well chosen, and examples from the history of caricature are added, to show his ancestors. But ideally Searle's work would have a more complete survey, and with wider comparisons. Then we might wonder if there's any clear distinction between cartoon and art.

Meanwhile, we can talk about his diverse originalities. There are his wildly grotesque transformations of the human head and body, which have influenced Scarfe and Steadman. Or there are his smart conceptions, often in the form of art-about-art jokes. A Bigger Slash: Hommage à David Hockey has a row of scrawny naked gents, peeing up arcs of multi-coloured piss into a West Coast pool – an exact bit of visual-verbal wit. Or there's a genre that is almost unique to Searle's practice, caricatural documentary: the draughtsman-witness-journalist visits Las Vegas or East Berlin, takes scenes with his pen, acid but humorous. The sour face of the border guard can't quite conceal the smirk of Nigel Molesworth.

Searle can do so many things, and blend them. But if there is one thing that he does essentially, and all through, it is to animate. He fills his subjects with a life. He finds it and then exaggerates it. Keats, in a letter, writes: "I go among the Fields and catch a glimpse of a stoat or a field-mouse peeping out of the withered grass – the creature hath a purpose and its eyes are bright with it – I go amongst the buildings of a city and I see a Man hurrying along – to what? The creature hath a purpose and his eyes are bright with it."

This is Searle's vision – a counterweight, perhaps, to the early death he saw closely and narrowly escaped. He brings out the vitality, and not only in creatures, whether human or animal, but in furniture, cars, architecture. Whether it's a jalopy, a shark-finned gas-guzzler, a rickety shantytown or a cathedral, he finds the action in the shape. His world is gesture. His eyes are still bright with it.

As a boy I was a huge fan of the Molesworth books, among them Down with Skool! and How to be Topp, written by Geoffrey Willans and illustrated, with grotesque relish, by Ronald Searle.

I loved them not only because they were funny and subversive, but because I was briefly sent to a hellish prep school myself, where the Dickensian headmaster, Mr Hancock, liked nothing better than putting small boys over his knee and giving them a ferocious spanking with an old gym shoe.

I assumed Searle was long dead, but, as any fule kno, he is alive and well and earlier this month celebrated his 90th birthday. He lives with his wife Monica in Haute-Provence, drinks champagne, or “engine oil” as he calls it, copiously, and is still working.

The Cartoon Museum in Little Russell Street, London WC1, is celebrating the great man, who is long overdue a knighthood, with a superb retrospective of his work over 75 years, beginning with his first cartoons as a teenager.

St Custard’s and St Trinian’s are both present and correct (“Hand up the girl who burnt down the East Wing last night”), but there are also many superb examples of his reportage. Chief among these are his visual record of his time as a Japanese prisoner of war after the fall of Singapore in 1942, including a period on the infamous Thai-Burma railway. His sketches, drawn secretly and hidden under the mattresses of dying men to prevent their discovery by Japanese guards, convey terrible suffering and cruelty with eloquence and economy. The study of a prisoner dying of cholera, in particular, strikes me as a masterpiece, seeming to catch the very moment when the last flicker of life departs the body.

The fact that after experiencing such horrors, Searle could produce work of such frivolity and fun is startling. Look out in particular for the picture of St Trinian’s girls dragging a lawn-roller in preparation for sports day that is clearly modelled on an earlier study of POWs hauling logs.

This is an exemplary exhibition, not only in the quality of the drawing, and the constant pleasures of Searle’s baroque imagination, but in its moving demonstration that the human spirit can survive the worst traumas mankind can inflict upon it.

Ronald Searle – a great affirmation of the human spirit

Ronald Searle encompassed both the tragic and the blissfully comic in his drawings, says Charles Spencer.

I loved them not only because they were funny and subversive, but because I was briefly sent to a hellish prep school myself, where the Dickensian headmaster, Mr Hancock, liked nothing better than putting small boys over his knee and giving them a ferocious spanking with an old gym shoe.

I assumed Searle was long dead, but, as any fule kno, he is alive and well and earlier this month celebrated his 90th birthday. He lives with his wife Monica in Haute-Provence, drinks champagne, or “engine oil” as he calls it, copiously, and is still working.

The Cartoon Museum in Little Russell Street, London WC1, is celebrating the great man, who is long overdue a knighthood, with a superb retrospective of his work over 75 years, beginning with his first cartoons as a teenager.

St Custard’s and St Trinian’s are both present and correct (“Hand up the girl who burnt down the East Wing last night”), but there are also many superb examples of his reportage. Chief among these are his visual record of his time as a Japanese prisoner of war after the fall of Singapore in 1942, including a period on the infamous Thai-Burma railway. His sketches, drawn secretly and hidden under the mattresses of dying men to prevent their discovery by Japanese guards, convey terrible suffering and cruelty with eloquence and economy. The study of a prisoner dying of cholera, in particular, strikes me as a masterpiece, seeming to catch the very moment when the last flicker of life departs the body.

The fact that after experiencing such horrors, Searle could produce work of such frivolity and fun is startling. Look out in particular for the picture of St Trinian’s girls dragging a lawn-roller in preparation for sports day that is clearly modelled on an earlier study of POWs hauling logs.

This is an exemplary exhibition, not only in the quality of the drawing, and the constant pleasures of Searle’s baroque imagination, but in its moving demonstration that the human spirit can survive the worst traumas mankind can inflict upon it.